When You Realize Why You Study History

- Gabrielle Bossy

- Mar 13, 2014

- 4 min read

Every once in a while, I think every historian gets in a slump and questions why they spend hours upon hours reading academic journal articles and books, writing lengthy essays and going to classes that can leave them feeling, let’s face it, depressed, and once in a while, bored. I remember experiencing this in my fourth year at Trent University. I was by no means bored, my classes were very engaging, but between reading about Stalin’s cruelty in one class, the Holocaust in another and the prison Abu Graib in the next, I was incredibly emotionally taxed and exhausted beyond belief. Although it’s unfortunate, it is almost necessary when this happens for a historian to detach oneself from what they are reading. When I’d explain this feeling to my parents or friends they would have one question- why? Why emotionally stress yourself out about the past? Why does this affect the present? Why do you want to be a historian with few job prospects when you leave university? I suspect they really knew the answer to why I did it and I suspect I did too but once in a while, when you’re up at 4 in the morning with 25% of your essay still to be written, you just question it anyways.

Then however, something usually happens to make you slap yourself on the side of your head and say “Of course I know why I study history!” It can be a book, a movie, a particularly interesting lecture, anything really but something will strike you to understand why you’re studying to be a historian. For me just recently, my revelation was meeting Elly Gotz for dinner and listening to his lecture here at Western University. For those of you who don’t know who Elly Gotz is, he is a self-proclaimed “business-man, entrepreneur and engineer” but on top of this he is a particularly engaging speaker and a survivor. Elly managed to survive Nazi persecution first in a Lithuanian Jewish Ghetto and then in Dachau- a Nazi concentration camp. He described the background of Nazi persecution in Lithuania (and as a student of Holocaust Studies I found this particularly interesting as it was an area I hadn’t really studied before), he told us of what he thinks the conditions for genocide are and he told us his personal tale of how he survived. In the end, it came down to a lot of luck and Elly, like many other survivors, recognized this.

Perhaps the most engaging part of Elly’s talk was the story of his small cousin Dalia. Because Elly was under the required age for slave labor but his parents and his aunt and uncle were not, Elly was often the one to take care of his one year old cousin in the ghetto. Soon, he felt as though he was her father, an immense attachment for a young teen to feel but under the circumstances it happened. However, as more deportations were leaving the ghetto with particular focus on very young children deemed useless by the Nazis, the parents of the child made arrangement for the child to be taken outside of Lithuania to keep her safe. They wrote to a relative who agreed to take the child with no compensation. However, the smuggling was dangerous. The baby was drugged by Elly’s mother so that she would not be conscious for a few hours. Next, Elly’s uncle put her in a duffel bag and took her with him to his work where he left her by a tree and she was picked up in the duffel bag by somebody who would smuggle her over the border. As a result of missing his cousin, somebody Elly saw as his daughter, he sank into a very deep depression. It was amazing to hear the lengths that people went to, to keep their loved ones safe. It made me realize how in instances of the biggest human indecencies you can see some of the greatest instances of hope and love in humanity. After the war, when Elly and his cousin both survived, they were able to meet each other once again! It was a truly amazing account.

Countless stories like this kept the audience engaged and on the edge of laughing and tears the whole time. Elly is certainly talented and puts his life story into really good use. At the end of his talk, Elly discussed the idea of Antisemitism and racism candidly. In his opinion there is no value in racism and it’s a mindless endeavor where humans prescribe a minority the same characteristics that they do other minority groups (money-hungry, dirty, dangerous). To him, it’s not even creative. It’s all the same. I couldn’t agree more. The stereotypes we use to persecute any number of different groups come down to the same characteristics. He ended by telling about his new life in South Africa with his children.

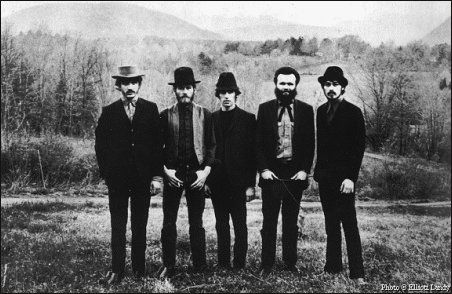

Elly Gotz with his cousing Dalia after the war. Photo from: http://www.crestwood.on.ca/ohp/elly-gotz/

He left as soon as he saw that his three year old was becoming racist because he felt the race relations there weren’t good. Although that is disheartening, it was nice to see that Elly learned from the hardships that he had in the past and ensured that his family would not be involved again or involved in acting as his perpetrators had. Although he could have had an immense amount of hatred in his heart and still could, he stopped his children from persecuting others and I think that speaks to his strength in an amazing way.

Comments